Semiconductor Tariffs. No Thanks, But If You Insist...

submissions by key ecosystem players are universally opposed to semiconductor tariffs..

On April 1, 2025, the Secretary of Commerce initiated an investigation under section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act (19 U.S.C. 1862) to determine the effects on national security of imports of semiconductors, semiconductor manufacturing equipment, and their derivative products, details here.

According to the document, this investigation includes, among other things:

Semiconductor substrates and bare wafers, legacy chips, leading-edge chips, microelectronics, and SME components. Derivative products include downstream products that contain semiconductors, such as those that make up the electronics supply chain.

Interested parties were then invited to submit written comments, data, analyses, or information pertinent to this investigation to BIS’s Office of Strategic Industries and Economic Security no later than May 7, 2025.

More specifically, the investigation was particularly interested in receiving information under the following categories:

(i) the current and projected demand for semiconductors (including as embedded in downstream products) and SME in the United States, differentiated by product type and node size;

(ii) the extent to which domestic production of semiconductors can or is expected to be able to meet domestic demand at each node size for each product type, and similarly the extent to which domestic production of SME can or is expected to be able to meet domestic demand;

(iii) the role of foreign fabrication and assembly, test and packaging facilities in meeting United States semiconductors demand, and similarly the role of foreign supply of SME in meeting domestic demand;

(iv) the concentration of United States semiconductors imports (including as embedded in downstream products) from a small number of fabrication facilities and the associated risks, and similarly the concentration of United States SME imports from a small number of foreign sources;

(v) the impact of foreign government subsidies and predatory trade practices on United States semiconductor and SME industry competitiveness;

(vi) the economic or financial impact of artificially suppressed semiconductor and SME prices due to foreign unfair trade practices and state-sponsored overcapacity;

(vii) the potential for export restrictions by foreign nations, including the ability of foreign nations to weaponize their control over semiconductors and SME supply chains;

(viii) the feasibility of increasing domestic semiconductors capacity (in different product types and node sizes) to reduce import reliance, and similarly the feasibility of increasing domestic SME capacity to reduce import reliance;

(ix) the impact of current trade and other policies on domestic semiconductor and SME production and capacity, and whether additional measures, including tariffs or quotas, are necessary to protect national security;

(x) what product types and node sizes could be built only using SME from U.S. companies;

(xi) what SME is manufactured abroad and faces limited competition from U.S.-made products;

(xii) what SME parts or components are only available outside the United States;

(xiii) where the U.S. workforce faces a talent gap in production of semiconductors, SME or SME components; and

(xiv) any other relevant factors.

Reading through this list of focus areas, it quickly becomes obvious that the word SME features prominently, actually in thirteen of the fourteen areas of investigation. SME in this context stands for Semiconductor Manufacturing Equipment, what we normally refer to as Wafer Fab Equipment (WFE).

The closing date for submissions was back on May 7 and now, you can now access those submissions here. All told, there were a total of 154 submissions from a wide range of companies and individuals. Prominent among the contributors were the likes of TSMC, Intel, Texas Instruments, Lam Research, Micron and the Semiconductor Industry Association. Notable by their absence were Apple, AMD, Applied Materials, KLA, Broadcom, Marvell, Cadence, Synopsys, OpenAI etc.

Before getting into the details of the key submissions, it’s worth pointing out that the US semiconductor industry offers rich pickings for those seeking to impose tariffs. Let’s take a few examples:

#1 Input Materials e.g. bare wafers, gases, chemicals etc.

These are almost all exclusively sourced from outside the US. In the case of silicon wafers, Japan leads the pack with Shin Etsu and SUMCO accounting for roughly one third and one quarter of global market share respectively. There is currently no US-based production of leading edge wafers, and only Globalwafers is working on a plan to change that situation.

When it comes to the multitude of high purity, high specification gases and chemicals that are essential for semiconductor manufacturing, Japan once again leads the pack with Taiwan and South Korea also playing an important role.

#2 Assembly/Test.

This is almost exclusively carried out in Asia, with Malaysia, China, Taiwan, South Korea and Vietnam featuring prominently. For example, US-headquartered Amkor, the global #2 OSAT vendor, is only now building their first ever facility in the US, co-located with TSMC in Arizona.

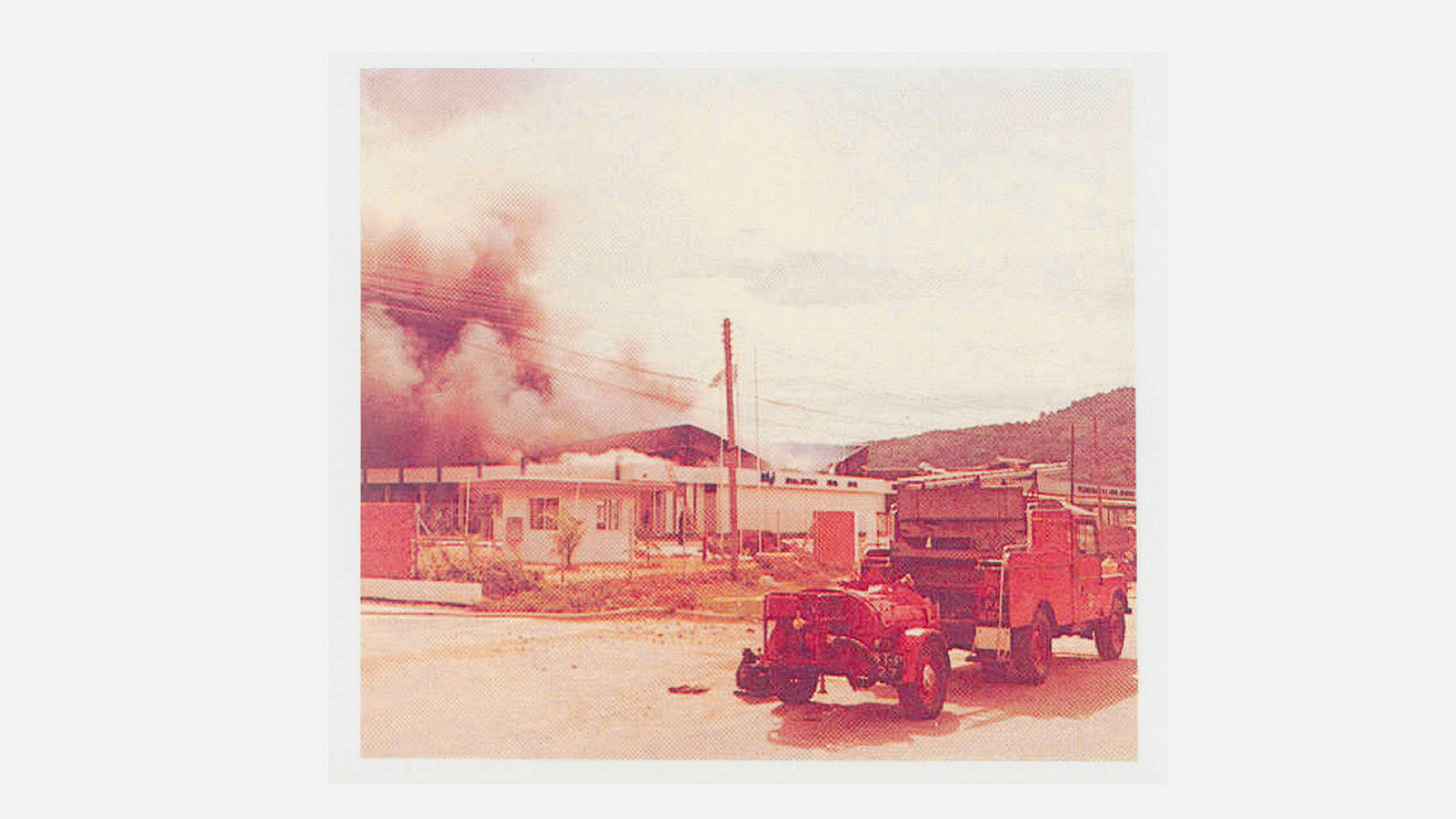

Intel opened their first assembly/test facility in Malaysia way back in 1972, details here. On a side note, the facility was destroyed by fire three years later, a disaster for Intel at the time, details here:

# 3 Wafer Fab Equipment (WFE or SME)

Here, US manufacturers are prominent, with Holland’s ASML and Japan’s Tokyo Electron also among the top 5 globally. The supply chain for WFE is incredibly complex and involves thousands of sub components sourced globally. Furthermore, the direction of travel in recent years for the US WFE players has been to expand in Asia, not in the US. For example, LRCX announced the opening of their largest ever facility in Malaysia back in 2021, details here.

It’s a similar story with Applied Materials, who just last year announced the doubling of their investment in Singapore, details here.

“We have over 2,500 employees here in Singapore today, and I believe there is a great opportunity for us to more than double the size of Applied Materials and create many great jobs here,” he told The Straits Times in an interview at the company’s office in Changi North Industrial Estate.

As for the reasons behind why the semiconductor industry evolved in this manner, a few key ones spring to mind:

#1 Historical. Semiconductor gas and chemical production grew out the the long established chemical industries in Japan (Shin Etsu) and Germany (Wacker, the original parent company of Siltronic)

#2 Cost. In the case of OSAT, the fact that it was, and still is albeit to a lesser degree, more labour intensive and less technically demanding, drove the business case for offshoring it to Asia.

#4 Market Access/Avoidance of tariffs/Local Incentives. The decision about where to build a semiconductor facility is a complex one, greatly influenced by a range of factors including gaining “free” access to local markets (e.g. Intel investing in Ireland), incentives offered by local governments (e.g. AMAT in Singapore, Intel in Ireland, TSMC in the US, etc..)

Against this backdrop, let’s now examine some of the key submissions and see if we can determine some common patterns that might point to where semiconductor tariffs will ultimately land..

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Semicon Alpha to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.